COVID-19 Vaccination: Israel, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain are Showing the Way Forward

By Patricio V. Marquez, Betty Hanan, Giovanni S. Marquez

“Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale”

–Rudolf Virchow, German physician, founding father of pathology and social medicine, 1821-1902

With the approval for emergency use of Pfizer/BioNTech’s and Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccines by the Stringent Regulatory Authorities (SRA) in the United Kingdom, Unites States, Canada, and the European Union beginning in early December 2020, different countries have started to roll out their COVID-19 vaccination campaigns.

While all of us are filled with optimism that the vaccines will help overcome the pandemic in a not-too-distant future and that we can then regain some normalcy in our lives, the critical challenge facing all countries continues to be how to ensure that “the most logistically difficult vaccination campaign in history” is conducted in the face of a limited supply of vaccines, at least one vaccine with “unprecedented cold chain requirements”, and a “hesitant and weary public”.

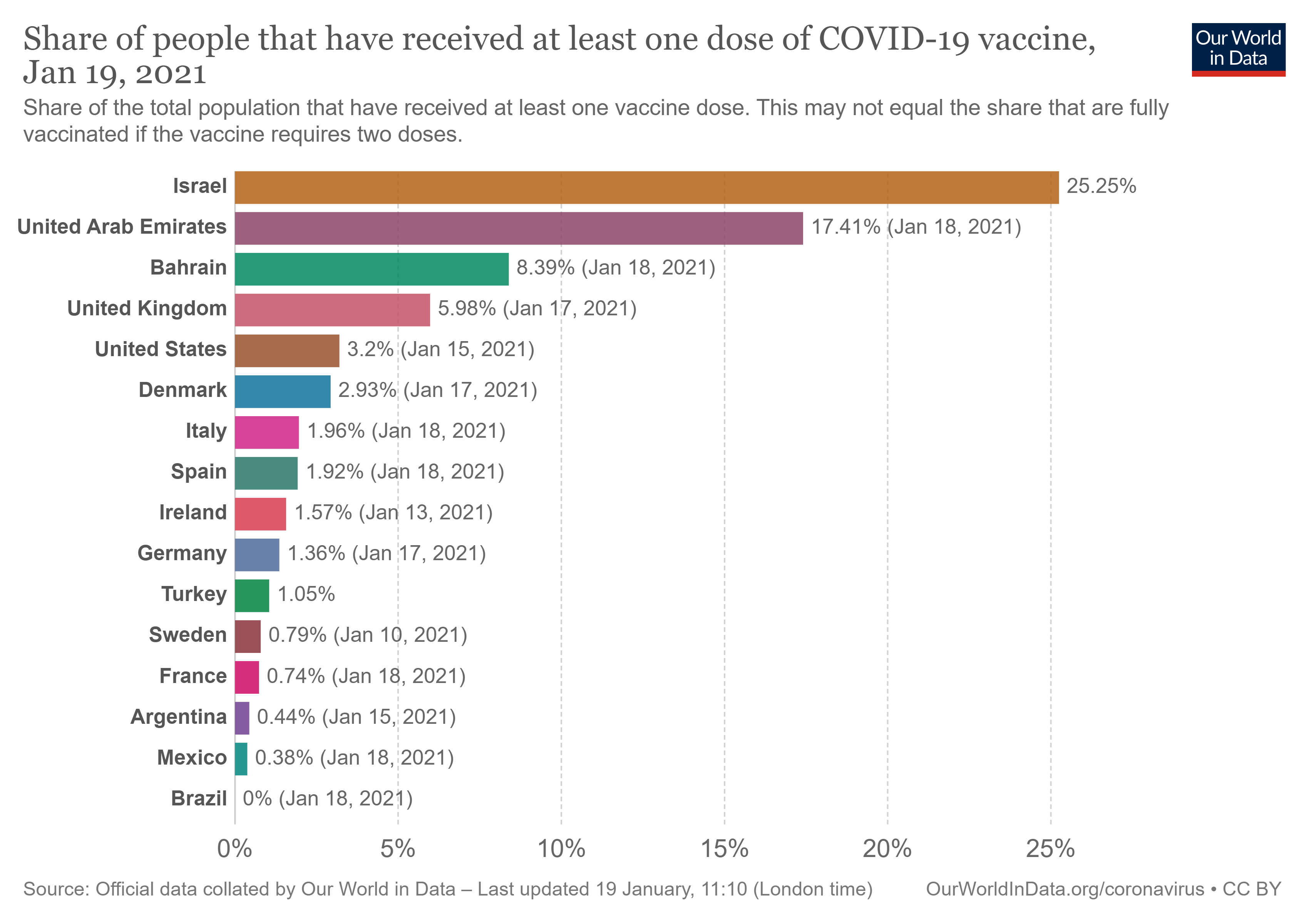

We think that other countries can learn from an examination of the structural and process building blocks underpinning the ongoing COVID-19 vaccination experience in three small Middle Eastern states–Israel, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Bahrain–that are currently leading the world in the vaccination effort. These are small countries with populations of between 1.5 and 9.3 million people. As shown in Figure 1, these states have administered the vaccine to 25.25%, 17.41%, and 8.39% of their populations, respectively, while the United Kingdom, United States, and Denmark trail further behind at 5.98%, 3.2%, and 2.93%.

What Needs to be in Place at the Country Level to Move from Vaccine Development to Vaccination?

The development of a new vaccine is not the end of the story. Rather, it is the beginning of a process to translate the potential benefit of a vaccine into immunity to a disease among the general population via inoculation of a pathogen or antigen that stimulates the production of antibodies. This requires well-planned, organized, adequately funded, and delivered public health services and programs in the mist of an ongoing pandemic.

The rapid and effective COVID-19 vaccination drive observed in Israel, UAE, and Bahrain is anchored on universal health coverage (UHC) arrangements that ensure that people have access to the healthcare they need without suffering financial hardship. These arrangements enhance both access and utilization and contribute to people getting vaccinated quickly.

In Israel, with the enactment of the National Health Law in 1995, health insurance became universal. Every resident is entitled to health insurance via one of the health funds (HMOs) based on an open enrollment scheme. The Law sets out a binding, itemized National List of Health Services (NLHS) which must be provided by each HMO to its members. The NLHS covers the total cost of service provision and prescription medicines.

In the UAE, made of up seven emirates, universal health insurance programs are well established. For example, under the ‘Thiqa’ health insurance program, the Abu Dhabi Government provides full medical coverage for all UAE nationals living in the emirate. Citizens get a Thiqa card, through which they get comprehensive access to a large number of private and public healthcare providers registered within the Daman network of health providers. Saada is a health insurance program for the citizens in the emirate of Dubai. It provides insurance coverage to citizens who do not currently benefit from any government health program. The program provides treatment through a large network of healthcare providers in the private sector and Dubai Health Authority (DHA) healthcare centers. Moreover, across the UAE, employers and sponsors are responsible for providing health insurance coverage for expatriate employees and their families, creating an important social safety net for the large immigrant population.

In Bahrain, a strategy has been implemented since 2014 to provide health insurance for nationals and expatriates working in both the public and the private sectors. A full package of comprehensive health services is provided for the whole population. Accessibility for all is maintained by the availability of free services and an established network of 27 health centers and specialized clinics staffed with family physicians.

Planning and Management

All three states have a clearly defined organizational structure and stakeholder involvement underpinning the Program Delivery Vaccination Core Activity to deliver and administer COVID-19 vaccines, including: (i) development of a national deployment and vaccination plan; (ii) identification of target populations; (iii) development and implementation of information/outreach campaigns related to vaccine merits and its deployment; (iv) use and deployment of real-time monitoring tools; and (v) strengthened national immunization budgeting and budget tracking capacity.

In Israel, an all-government effort to support the vaccination effort was launched in December 2020. The vaccine developed by Pfizer and its German partner BioNTech is being administered. Israel’s health ministry authorized in early January 2021 the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Moderna. The first stage of vaccination prioritized healthcare workers, the over-60s, and groups considered at risk by virtue of either their age, health, or occupation. Next, priority was given to teachers, who were eligible for vaccination after a decision that schools would resume normal service in the second half of January 2021. Initially, only large vaccination centers were opened in central locations. Later, smaller neighborhood sites – key parts of the vaccination drive – were set to open to ensure that the vaccine was accessible to everyone. By mid-January 2021, 250 sites were expected to be operating throughout the country.

An issue that has been raised about Israel’s vaccination program is that while it is covering Israeli citizens over 16, including its Arab citizens and Palestinians residing in East Jerusalem, it perhaps should assist the vaccination effort for Palestinian people living in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. While the 1990s-era Oslo accords grant the Palestinian Authority limited self-rule in the West Bank and the Gaza strip which are controlled by the group Hamas, the expectation is that both sides may cooperate in combating infectious diseases as a critical global health security action to prevent the spread of disease. The Palestinian Authority expects to receive vaccines under COVAX, as well as part of possible agreements with AstraZeneca, Moderna, and the Russian-made Sputnik V vaccine.

In the UAE, the free vaccine program aims to protect both citizens and foreign residents, so anyone living there can get the COVID-19 vaccine. There are two vaccines in the UAE for use on eligible individuals against the COVID-19 infection: one by Sinopharm and the other by Pfizer-BioNTech.

Bahrain began in November 2020 inoculation of front-line workers as well as some senior officials, prior to completion of Phase III trials of the with BBIBP-CorV (a vaccine developed by the Beijing Institute of Biological Products and put into trials by the Chinese company Sinopharm). Bahrain formally launched its vaccination campaign in December 2020. All citizens and foreign residents of Bahrain are eligible to receive the vaccine. Registration for a vaccination appointment can be completed online or via a smartphone application.

Supply and Distribution

Key activities under the Supply and Distribution Vaccination Core Activity include: (i) procurement of COVID-19 vaccines, vaccination supplies, and PPE for vaccinators; and (ii) logistics and cold chain.

Israel and parts of the UAE, which are using the vaccine developed by Pfizer/BioNTech, need to store this vaccine at -70 to -80 degrees Celsius. Short distances in these small countries are key to preventing spoilage during transit. In Israel, vaccine vials, which were stored in a very cold deep freeze, are delivered in batches of 195 vials, providing a total of 975 doses. As vaccines can only be kept for four days after defrosting, every location where the vaccine is deployed has to administer the vaccines to almost 250 people daily.

Bahrain was the second country in the world to approve the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, approved China’s Sinopharm vaccine in November 2019, and is speeding up the effort to vaccinate its population to reach herd immunity using its centralized, well-staffed health care system.

Beside using their logistical capability to support their own vaccination efforts, Abu Dhabi and Dubai are using it to serve as a hub for global vaccine distribution. For example, Abu Dhabi Ports is supporting this effort with a 19,000-square meter temperature-controlled warehouse facility in Khalifa Industrial Zone. The UAE is also is in partnership with SkyCell, a Swiss firm, to produce refrigerated shipping containers that can keep doses cold in transit. Dubai Airports and GMR Hyderabad have announced the creation of a COVID-19 vaccine distribution corridor with capacity to handle up to 300 tons of vaccines per day. The corridor connects major vaccine manufacturers in India with markets around the world via Dubai’s cargo hub.

Program Delivery

Key activities under the Program Delivery Vaccination Core Activity include: (i) implementation of a national risk-communication and community engagement plan for COVID-19; and (ii) ensuring that vaccines reach the target populations. In the three countries, healthcare data are centralized and digitized effectively, facilitating citizens to either access an app or call a hotline and receive an immediate appointment for vaccination if they are eligible.

Health authorities in the three countries have enlisted the support of religious leaders to mobilize their communities to get vaccinated. For example, Israeli health officials consulted with ultra-Orthodox media and community leaders, although there is still a lack of trust among Muslim Arab and Christian minorities there. UAE’s Fatwa Council issued an Islamic ruling in favor of the vaccine, and its chairman was vaccinated in public. The Prime Minister became the first Israeli to be vaccinated live on TV. The Prime Minister of the UAE and the King of Bahrain have also been vaccinated to encourage others to follow in their footsteps. While the Prime Minister of the UAE announced his vaccination via Twitter, scores of Emirati officials, among them the health minister and the ruler of Dubai, have posted photos of themselves receiving the vaccine.

In Israel, the government has also stepped up its efforts to target disinformation about possible vaccine’s side effects or other risks, with medical professionals on TV reassuring people that the vaccine is safe and effective. At the request of the government, Facebook took down four groups at the start of the vaccination drive that had disseminated texts, photographs, and videos with content designed to mislead consumers about COVID-19 vaccines. There are incentives beyond the inoculation itself. Israel is set to become the first country to start issuing a “green passport” to residents who have received the full two-dose vaccine – effectively a passport out of lockdown. The certificate will allow residents to travel abroad without a PCR test, exempt them from some mandatory quarantines, and offer access to cultural events and restaurants when the current national lockdown has been lifted.

In Israel, health facilities across the country are involved in the vaccination effort. The army enlisted about 700 paramedics to help administer the vaccine ensuring prompt deployment. The vaccination drive began on December 20, 2020. The government aimed to reach a vaccination rate of around 150,000 people a day within a week, and to have inoculated over two million people by the end of January 2021. As of January 7, 2021, the Israeli Health Ministry informed that 17.5% of the population – and 70% of citizens aged 60 or older – had received their first shots. The country’s highly digitalized healthcare system has helped speed the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccination drive in Israel. All citizens over 18 must be registered with one of four competing non-profit health insurance plans – known as Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs). As soon as the vaccine became available, text and voice messages were sent to eligible groups of people telling them to make an appointment. If a person has forgotten or overlooked the appointment, they can simply call their HMO, give their ID number and receive an appointment close to their location often for the following day.

In the UAE, Abu Dhabi Health Services Company, (SEHA), the UAE’s largest healthcare network, has opened two COVID-19 vaccination centers in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi and one in Dubai to administer the Sinopharm vaccine. Other SEHA facilities are also administering the vaccine.

In Bahrain, registration for a vaccination appointment can be completed online or via a smartphone application. The government has also launched mobile units providing home vaccinations against COVID-19 for the elderly and people with special needs.

Some Observations

As the experience of Israel, UAE, and Bahrain shows, political support at the highest levels of government is critical to translate plans into sustained action to achieve clearly defined, measurable targets. Collaboration and integration of public health and primary care leverages and strengthens the capabilities of a country to deliver vaccinations and to achieve national vaccination coverage targets, although possible delays in any deliveries of vaccines will slow down the rate of vaccination and hence the achievement of targets defined in country plans. While many countries in the West have detailed rules that define priority groups for vaccinations, which can slow distribution, Israel’s has a relatively broad initial eligibility criteria, and both the UAE and Bahrain offer them to all-comers—this option, however, is limited to few countries that have that sufficient vaccine supplies to cover their entire population. The use of broad eligibility criteria may have helped facilitate rapid scale-up of vaccine administration in the three countries, but a potential trade-off is the risk that a broad initial target population will delay access for those who may benefit most from vaccination and/or have least access to healthcare.

Besides having vaccines authorized or approved for administration to the general population, vaccine doses must be supplied. Vaccination requires that vaccine doses must be transported to sites of administration under quality-assured, appropriately temperature-controlled conditions; there must be equipment to administer vaccines; people need to be able to register to get vaccination appointments and must be able to access administration sites. Supplemental personnel, including active recruitment of volunteers and retired health personnel, has helped to alleviate the strain on overworked healthcare staff facilitating effective vaccination efforts. Innovative methods are also needed to step up the vaccination drive, locating vaccination centers closer to where the population lives and works.

The experience of Israel shows that investing in good digital infrastructure to process and centralize large volumes of health data—like who to vaccinate, shares of immunized people in a given area—provides data and information in real time for program planning and monitoring.

Disease surveillance, prompt patient identification, diagnosis and isolation of all cases, contact tracing, and surveillance of contacts, supported by diagnostic virology laboratories, are critical tools to complement the vaccination effort as the future challenge will be to maintain the interruption of COVID-19 disease circulation over time. Pharmacovigilance systems need to be strengthened to monitor and document on a continuous basis on all reported adverse reactions occurring during and after COVID-19 vaccination and to prioritize for investigation all suspected serious adverse reactions.

Effective public communications and public buy-in are also critical elements of an effective vaccine campaign. The experiences reviewed clearly signal the importance of strengthening risk communication and community engagement, with a focus on increasing awareness of COVID-19 prevention and to strengthen strategic communication addressing demand-side challenges for vaccine uptake, particularly among minority communities who are more skeptical of the vaccine. Such communications efforts need to address specific national knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about vaccination, including methods that resonate with the local audience, get them on board, and earn their confidence. As it has been done in the three countries reviewed above, showing high level political figures receive their vaccines helps reduce vaccine hesitance.

As the development and rollout of safe vaccines for Covid-19 proceeds, helping to eventually achieve herd immunity, a critical factor to stress is the need for governments to continue to support essential public health measures such as the use of masks, hand hygiene, and physical distancing. These are highly cost-effective measures that complement vaccines in the fight against the pandemic, reducing the spread of the coronavirus and preventing disease and death.

This article first appeared on pvmarquez.com: COVID-19 Vaccination: Israel, United Arab Emirates, and Bahrain are Showing the Way Forward | Patricio V. Marquez (pvmarquez.com)